Mark Redd

3 - CLI

Wait, this isn’t Python!

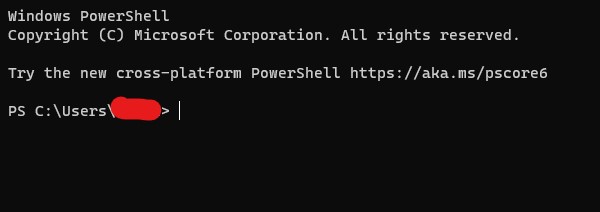

You’re right. You will run most of your code from something called the “Command Line Interface” (CLI) or “terminal”. There are many other names for this but I will use “terminal”, “CLI” or just “command line” to mean the same thing. You may have seen it before. It looks like this:

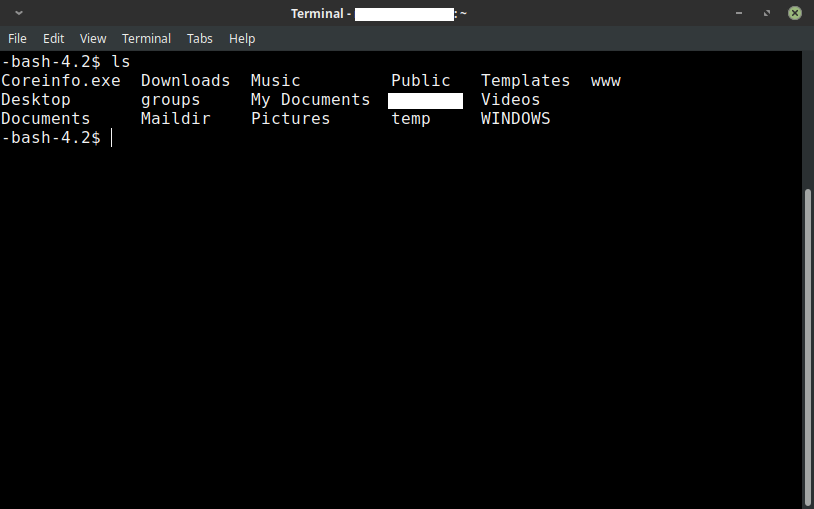

Or this:

Okay, why are we talking about this?

You will use the CLI to run Python programs in this book so this section is to familiarize you with how the CLI works.

This used to be the only way to use a computer. If you wanted to find files, play a game, or use any program, this was how you did it. No mouse, no windows, just you and some text on a black screen. The CLI allowed you to enter text commands into the prompt (seen above as the text after the $) and responded with more text. We will be doing similar things in this lesson.

But first, a vocabulary lesson

If you aren’t already, you should be familiar with basic terminology relating to file systems. Important words you need to know are in bold font (i.e. words like folder, file, program and app or application”). I will use the words directory and folder interchangeably.

All file systems I have seen start with a root folder (usually C:\ for Windows and / for macOS and Linux). File systems start at this root folder and the root folder contains a tree of sub-folders in which all files are organized. You will sometimes see folders referred to as parent folders to their sub-folders and their sub-folders as child folders to the parent folder. This relationship is a common way of understanding relationships between files and folders. The address of a particular file or folder is called its path. The path of a file or folder is a string of text with each folder name separated by \ (for Windows) or / (for macOS or Linux). Examples of paths are:

C:\Users\mer\Documents\a_file.py(Windows)/home/mer/Documents/a_file.py(macOS or Linux).

Okay now let’s use the command line!

We will cover how to do basic navigation and commands in the CLI. The command line can actually do a TON of stuff so this lesson is by no means comprehensive. It is intended to get you just competent enough to do programming.

Open the command line

Depending on your operating system (e.g. Microsoft Windows, Apple macOS, Linux) the way to open your command line differs significantly. Once your command line is open however, almost everything else is the same or very similar. I will indicate the differences where this is the case.

Windows

- From your desktop, press the windows key.

- The start menu should pop up.

- Type in “powershell” into the start menu search bar

- A bunch of options should be displayed in the start menu.

- Select “Windows PowerShell” from the list of options to open it.

- A blue box with some text and a prompt should appear that looks something like this:

PS C:\Users\YOUR-USERNAME\>

- A blue box with some text and a prompt should appear that looks something like this:

Apple macOS

- Open spotlight search by pressing ⌘+Space.

- A spotlight search bar should appear on your screen.

- Type “terminal” into the search bar.

- Options should appear under the search bar.

- Select the “Terminal” application to open it.

- A white box with some text should appear with a prompt that looks something like:

"YOUR COMPUTER'S NAME":~ "YOUR USERNAME"$

- A white box with some text should appear with a prompt that looks something like:

Linux

- Press

ctrl+torctrl+alt+tfrom your desktop.- A bash window should appear with some text in it and a prompt that looks like:

"YOUR USERNAME"@"YOUR COMPUTER'S NAME" ~ $or-bash-4.2$

- A bash window should appear with some text in it and a prompt that looks like:

Note about your command line prompt

Regardless of what kind of prompt appears on your command line interface, ignore everything on the line before the $ or the >, that is, the prompt symbol. That part before the prompt symbol is usually irrelevant to understanding what is happening anyway. In this lesson and the rest of the book, I have omitted anything before the prompt symbol and you may interpret the $ or the > as being equivalent. Therefore, when you see something like $ clear written in the book, you should read that as, “Type the text clear into the command line prompt and press enter.” Just remember, the $ is NOT part of what you type in.

Once you have successfully opened your command line interface, you may begin the rest of the lesson. The object of this lesson is to practice and become familiar with each of the commands listed below. A summary table at the end of the lesson lists all the commands and what they do.

Where am I? (Command: pwd)

Begin by typing the following in your prompt and pressing Enter (Remember, DO NOT type in the $.):

$ pwd

pwd means ‘print working directory’. This command will show you where you are

in the directory structure of your computer. For example typing this command

into the terminal on my linux computer print out /home/mer to the terminal window, which tells me

I am in the ‘mer’ directory of the ‘home’ directory of the root directory of my

computer. Similarly in Windows, pwd returns C:\Users\YOUR-USERNAME\. Therefore if you ever get lost while navigating in the terminal, use pwd to

figure out where you are.

Moving Around (Command: cd)

Type the following into your terminal and press Enter (Again remember, DO NOT type in the $.):

$ cd ~

cd means ‘change directory’ and is one of the main ways you will navigate

the command line. The normal usage of the “change directory” command is of the form: $ cd "NAME OF DIRECTORY" (e.g. cd Documents) but in this case we are using the “home” shortcut (~).

The tilde (~) is a shorthand that stands for the ‘home’ directory. This can take you to slightly different places depending on the operating system you are running, but should be the default starting place for any folders you may wish to navigate. If you

need to get back home or want to navigate from the home folder as a root

folder the ~ will get you there.

So when you enter cd ~ what you are telling the terminal is this:

“Take me me to the home folder.” Or “Change the working directory to the home folder”.

Working in folders (Commands: ls, mkdir, and touch or New-Item)

Now that you are in the ‘home’ folder, enter the following:

$ ls

ls is shorthand for “list files and sub-folders in the current directory”.

Upon entering this command you should see a list of files and directories in

your home folder.

Let’s make a directory in your home folder. Enter the following:

$ mkdir peas

Now enter the ls command and you will notice a new folder in your home folder

called ‘peas’ you made it with the ‘make directory’ command.

Let’s go in there!

$ cd peas

$ ls

$

If you type in the above commands in you will notice that nothing comes up! There is nothing in this folder yet so lets make a file to put in this folder! This is bit different for Windows so follow the Windows commands if you are using Windows.

- Command for macOS or Linux

$ touch carrots.py

- Command for Windows

> New-Item -type file carrots.py

You have just created an empty file called carrots.py. The .py part of the filename is called the extension and is a way that a user communicates what kind of file is being used. Generally, Python files have the .py extension but they are not fundamentally different from plain text files (i.e. files that end with .txt).

Make another file called cool_beans.txt using the touch command (if you’re on macOS or Linux) or New-Item command (if you’re on windows). Go on, try it yourself!

Did you do it? Check that you it worked using the ls command.

You should see that you have two files in this folder called carrots.py and cool_beans.txt. If you’re curious you can

“print the working directory” and find this folder in your file explorer

program on your computer. Cool huh?

Now that we know how to create files and folders we will now learn how to delete them.

Deleting Files and Folders (Commands: rm, rmdir)

Now that we know how to create files and folders we will now learn how to delete them. Let’s delete your files by entering the command:

$ rm carrots.py

rm means “remove”. Verify that this has been deleted with ls.

Now let’s delete the other file.

$ rm cool_beans.txt

When you finish this your directory should once again be empty. You can verify

this with ls.

Using Relative Paths (e.g. . and ..)

Now…how do we get out of here? You may want to go directly to the home directory using

$ cd ~

but you may not always want to go all the way back to the home directory when all you really want is to go to the next highest directory in the folder structure (a.k.a. the “parent directory”). I will now show you the way to do this. Simply enter:

$ cd ..

This is a shorthand for, “change directory to the immediate parent directory” using what is called its “relative path”. In the command line, . is shorthand for “the directory I’m in right now” and .. means “the immediate parent folder of where I am right now”.

You can verify that you have indeed left the peas directory by using the pwd

and ls commands. Now it is time to actually delete the directory.

$ rmdir peas

If you didn’t have any errors doing this congratulations! You have finished the basic exercises for the command line!

Did you get all that?

Below is a table of all the commands we learned in this lesson and pertinent information about each.

| Command | Usage | Effect |

|---|---|---|

pwd |

$ pwd |

“Print Working Directory”: Prints the location of the folder you are currently in. |

cd |

$ cd NAME |

“Change Directory”: Changes your location to that of NAME. The tilde ~ refers to the home directory, . refers to the current directory and .. refers to the immediate parent directory. |

ls |

$ ls |

Lists all files and sub-folders in the current directory. |

mkdir |

$ mkdir NAME |

“Make Directory”: Makes a directory in the current directory called NAME. |

touch |

$ touch NAME.EXT |

(Mac and Linux) Makes a new file in the current directory with a name of NAME and an extension of .EXT |

New-item |

> New-Item -type file NAME.EXT |

(Windows) Same as touch. |

rm |

$ rm NAME |

“Remove”: Permanently deletes the file called NAME where NAME includes both the filename and the extension. |

rmdir |

$ rmdir NAME |

“Remove Directory”: Permanently deletes a directory called NAME. (Only works if the directory is empty.) |

| current directory path | cd . |

Takes you nowhere but . is the shorthand for “the directory I am currently in”. |

| immediate parent directory path | cd .. |

Takes you to the immediate parent directory. For, example if you were in /home/mer/cheese/pizza/ and you entered cd .. you would be taken to /home/mer/cheese/. Remember that .. is shorthand for “the immediate parent directory”. |

Memorize these commands or keep this cheat sheet with you to help you work in the command line. Once you feel comfortable with these commands then it’s time to start programming!

Hone your skills

Here are a few questions you should research:

- Normally you have to remove every file in a directory before you can delete the directory. What is a way you can delete a directory and all its contents using one line of command line code? Why would you not want to do this?

- How could you navigate to the parent directory’s parent’s parent directory in one command?

- Look up commands to ‘copy’, ‘rename’ and ‘move’ files in command line. How would you complete these common tasks in command line?

- Research other common commands in command line and learn them for your benefit. Use google or a similar search engine. There are many good tutorials to use many powerful commands in the command line.

- It can be a pain to navigate in the terminal. Can you use some sort of autocomplete it the terminal?

- It can be a pain to find your files and then have to navigate to the folder in the terminal. Can you figure out how to simply open a terminal in a chosen folder using the file explorer menus?